Thanks to Maria and thousands more like her across the continent, Africa can look forward to a healthier future.

About 10 years ago, the African country of Djibouti had nearly succeeded in wiping out malaria. The country’s leaders hoped that getting rid of the disease would help them attract new investment, development, and tourism.

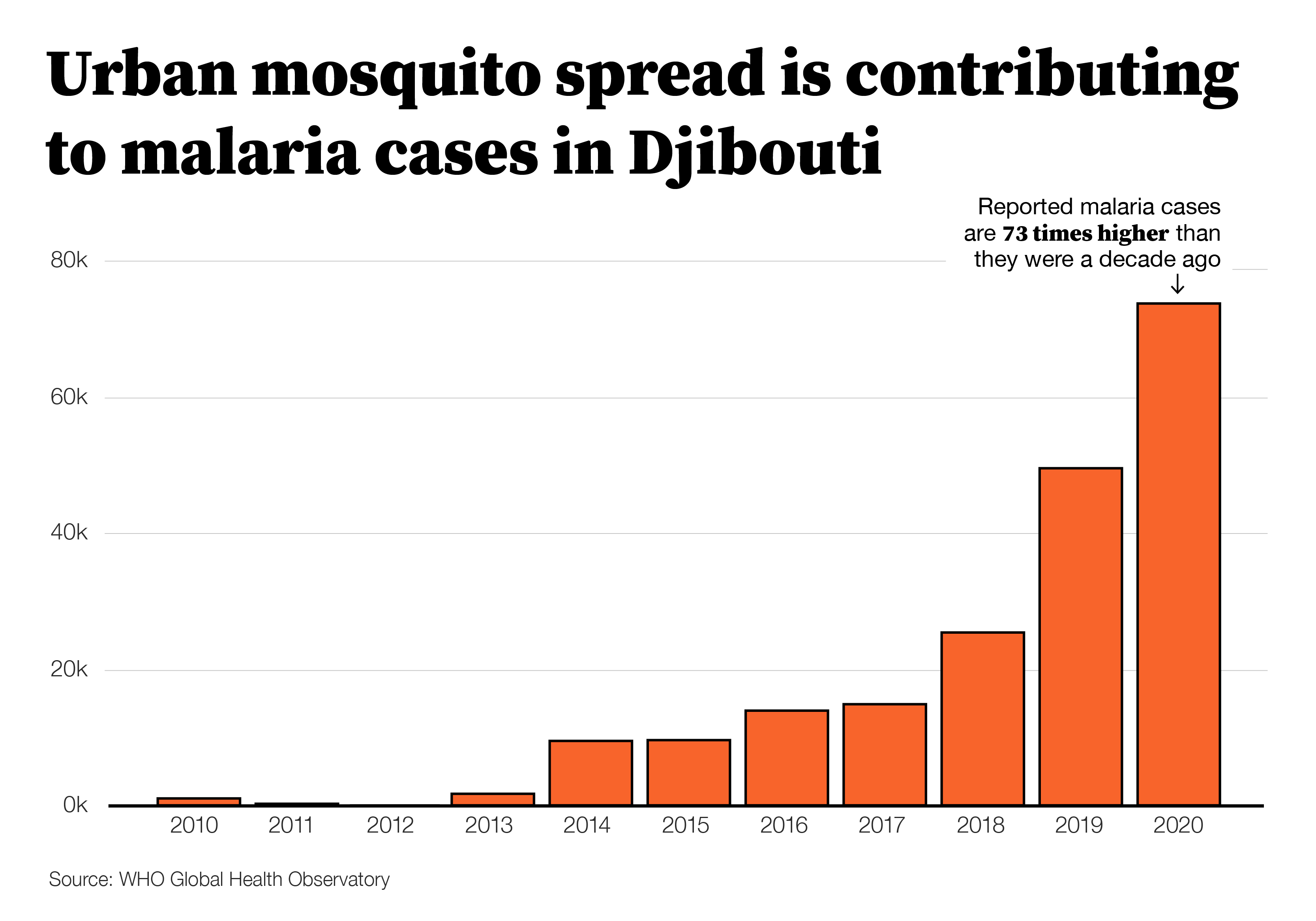

Then suddenly the disease roared back. Cases surged from just 27 in 2012, to more than 73,000 in 2020—a huge number for this East African nation of just one million people.

The cause?

A highly invasive mosquito that had migrated from South Asia and the Arabian Peninsula into Africa.

This pest—the Anopheles stephensi mosquito—has now emerged as one of the biggest threats to malaria elimination in sub-Saharan Africa. Since establishing a beachhead in Djibouti, An. stephensi mosquitoes have been detected in Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, Kenya and as far away as Nigeria and Ghana, in West Africa. According to one study, if this mosquito is left unchecked an additional 126 million people on the continent will be at risk of malaria.

What makes An. stephensi particularly dangerous is where it has chosen to reside. Unlike other malaria-carrying mosquitoes in Africa that primarily breed in rural areas, An. stephensi thrives in urban environments. Cities are already home to 40 percent of the population in sub-Saharan Africa and continue to experience rapid growth, creating a fertile habitat for this mosquito. Making matters worse, An. stephensi has been found to be resistant to many of the insecticides used to control mosquito populations. And they bite in the evening before bedtime—not in the middle of the night like other mosquitoes—making bed nets less effective as protection.

But this story doesn’t end here.

In 2018, the government of Djibouti, in search for a new approach to combat these urban invaders, heard about a biotechnology company called Oxitec that has a potentially game-changing solution to mosquito control.

The fight against mosquitoes and the diseases they carry has always been a game of cat and mouse. Humans develop new interventions—like bed nets, insecticides, and treatments—to protect themselves from mosquitoes. Mosquitoes, meanwhile, have an incredible capacity to adapt, allowing them to eventually dodge or develop resistance to the latest control methods. Then humans respond with more innovations to outsmart the mosquitoes. And so on.

Oxitec, however, aims to change this game from cat versus mouse to mouse versus mouse. Or in this case, mosquito versus mosquito. Oxitec specializes in using mosquitoes to fight other mosquitoes. With its genetic technology, Oxitec has already developed mosquitoes to effectively combat the dengue fever–carrying mosquito, Aedes aegypti, in Brazil. Now Oxitec plans to use the same technology to help African governments control An. stephensi and reduce the spread of malaria.

Here’s how Oxitec’s technology would work against An. stephensi mosquitoes: Oxitec male mosquitoes carry a special gene to prevent their female offspring from surviving into adulthood. (Only female mosquitoes bite and spread malaria.) Released into the wild, the male Oxitec mosquitoes mate with wild female mosquitoes. All the female offspring die. All the male progeny, which don’t bite, will survive and go on to mate with other wild females. With sustained releases of male Oxitec mosquitoes, more females die off, dramatically reducing the mosquito population and the spread of malaria. After the mosquito releases stop, however, because half of the gene’s carriers (the females) cannot survive, the gene steadily declines and disappears from the mosquito population within a few generations.

Genetic technology like Oxitec’s understandably raises many questions. Is it safe? What are the lasting environmental impacts? Here’s what’s important to know:

Because it’s passed through mating, the gene the Oxitec male mosquitoes carry only targets the An. stephensi mosquitoes. It doesn’t have any impact on other insects and cannot be established in the local ecosystem. After evaluating the potential risk of genetically modified mosquitoes, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2016 and the EPA in 2022 have confirmed that the Oxitec mosquitoes do not pose a threat to humans or the environment. More than one billion Oxitec mosquitoes have been released worldwide, with no negative impacts. In Brazil, the Oxitec Aedes aegypti mosquitoes have been so successful in reducing the spread of dengue fever that they are in demand by communities, governments, and businesses in Brazil. Homeowners can even buy a kit to raise the mosquitoes in their own backyards. (If you want to learn more about this technology, I encourage you to visit the Oxitec website and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Last year, the government of Djibouti formed a partnership with Oxitec, Association Mutualis (a non-profit public health organization in Djibouti), and the Djibouti National Malaria Control Programme to use this new technology to defeat An. stephensi.

No Oxitec mosquitoes have been released in Djibouti during the current pilot phase of the project. But the government of Djibouti expects to move forward with the first releases of Oxitec mosquitoes next year in Djibouti’s capital city, where 70 percent of the population live.

This solution is being pursued with the support of the people of Djibouti. The government of Djibouti, Oxitec, and its local partners have been working together to educate and engage the public about this technology, going door to door to listen to their concerns, and ensuring all the communities’ questions have been addressed before moving forward with the release of the mosquitoes. Local support has been outstanding to date.

To end malaria, we need many new tools and innovations to reduce the burden of this disease and move the world closer to eradication. I’m excited about the potential of Oxitec’s technology to help Djibouti and the rest of Africa achieve this goal.