The Code Breaker is highly accessible for non-scientists. And that’s super important, because the ethics of CRISPR’s use are not clear.

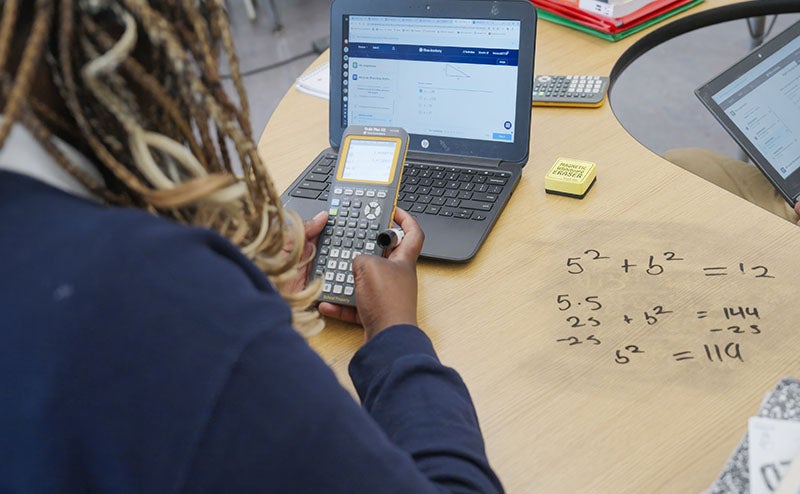

If you haven’t directly experienced the pandemic’s impact on education—the months of learning that students have tragically lost, and the disproportionate impact on low-income students—you almost certainly have heard about it. What gets less attention, but is just as important, is COVID’s impact on teachers. Because of the strains created by the pandemic, more educators than ever are thinking about leaving the profession, and the rates are especially high among the most-experienced ones. As veteran teachers leave, more responsibility will fall on ones who have spent less time in the classroom. In short, there has never been a more important time to support teachers.

Even before the pandemic, supporting teachers was a core part of the Gates Foundation’s work in U.S. education. And this year marks the tenth anniversary of a project I fund personally, separately from the foundation, that has also learned a lot about that subject. It’s called the OER Project (OER is short for Open Educational Resources), and for the past decade, the team there has been creating free online courses and professional development for educators. Although OER courses won’t solve every problem that the pandemic has caused for schools, they’re an important part of making sure teachers get the support they deserve—and students get the high-quality curriculum they need—in such difficult times.

Broadly speaking, there’s nothing new about the concept of OER. Educators have always curated their own classroom materials. Every teacher who has ever downloaded a worksheet from Pinterest has used an open educational resource.

What makes the OER Project different is that it is far more than worksheets and videos. It offers complete courses, including the equivalent of online textbooks for students, coupled with instructional support and professional development for teachers. Every course is available free, online, for any educator who wants it. All of the content is aligned to state standards and created by well-known subject-matter experts and master teachers. (Here’s a list of the OER Project’s creators and advisory board of scholars and historians. Although I fund the project, I am not involved in creating the content.)

In the past decade, the OER Project’s first two courses, Big History and World History, have reached more than 1 million students and 20,000 teachers around the world. And the team has just launched two new courses: a yearlong Advanced Placement World History class and a three-week course on climate change.

This video, which ties the war on Ukraine to the history of agricultural productivity, gives you a glimpse of how Big History helps students connect the present to the past:

(Other examples from the OER Project include a video about climate change and one about smallpox, featuring the eminent epidemiologist Larry Brilliant.)

To see how effective these courses can be, look at Big History’s impact on students’ writing skills, and particularly how it helps close the gap between high- and low-income students. At the beginning and end of the school year, teachers who use the course get a measure of how well each of their students is writing. According to the OER Project’s internal data, on average, only 26 percent of the students taking Big History in low-income schools start the academic year rated “proficient” or better in writing. By the end of the school year, that number has jumped to 62 percent—which is roughly on par with Big History students at private schools.

What’s more, teachers say they like the material. It’s being used in more than 2,200 schools, and last year, 95 percent of teachers who taught a course from the OER Project said they would recommend it to their students. And more states are encouraging school districts and teachers to use online educational resources, including those from the OER Project.

“We would love for many others to get involved and keep raising the quality of digital tools.”

Given the success we’ve seen, I’m quite optimistic about the broad impact that OER materials can have in education. The project reached 1 million students in its first decade; a decade from now, I hope it can be reaching 1 million students every year. But our goal is not for the OER Project to be the only source of open educational resources, or even the biggest. We would love for many others to get involved and keep raising the quality of the digital tools that teachers can use. A great goal for the entire field would be to create courses and professional development for every subject and every grade. The potential here is enormous.

As more people create open educational resources, there are a few lessons from the OER Project that are worth keeping in mind. For one thing, regardless of what course or grade you’re talking about, the content needs to be developed by experts in the field and in classroom education.

In addition, teachers need supports that help them do their best work. New teachers might need assistance with, for example, teaching reading, while veterans might appreciate hearing from university faculty discussing the latest research. And the need for support became painfully obvious when COVID-19 struck, as teachers had to figure out how to use new digital systems, keep their students engaged while online, and deliver hybrid instruction. High-quality materials that can be delivered digitally and safely weren’t a luxury; they were a necessity. But they were in short supply.

The OER Project was able to offer on-demand professional development, virtual training sessions, and an online community where teachers can share ideas and resources. If a new teacher posts about trying out a new lesson from the OER Project, a veteran will follow up in a few weeks and ask how it went. It’s a simple but powerful way for educators to spread best practices.

The last and possibly most important lesson is that content needs to be revised according to feedback from the teachers who are using it. After all, they are the ones who know the most about what works for their students and what doesn’t. And the more invested they are in the course, the more effectively they’ll teach it.

This is one of the big advantages of working with digital content: It can be updated more frequently than print publications can. Many textbooks are notoriously out of date. One teacher told the OER Project team that her textbooks on current events still refer to the Soviet Union! The difference between print and digital is like updating your software using floppy disks that come in the mail versus simply updating an app on your phone.

I know that choosing a curriculum and textbooks can be a complicated process. But it is hard to argue with the core insights of the OER Project’s work. Courses should be created by educators and subject-matter experts, supplemented with professional development, and regularly improved with feedback from the teachers who use them. In the growing field of open educational resources, the curriculum publishers who keep these principles in mind will be in the best position to succeed.

All of the OER Project’s materials are available free on its website.