If we’re going to make sure that COVID-19 is the last pandemic, we need the GERM team.

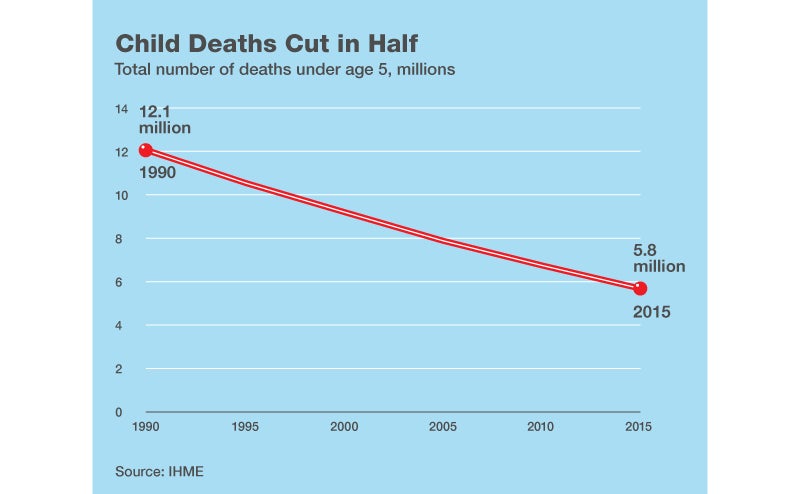

Of all the charts I’ve seen, this one is the most beautiful:

Why?

First, that descending red line captures one of the most amazing stories of human progress: It shows how the number of deaths of children under 5 per year has been cut in half since 1990.

Second, hidden along that line are millions of stories of the incredible work being done by health officials, governments, donors, and parents around the world to help save all those lives.

Here’s one of those stories. It begins with some remarkable women I met in Ethiopia. They are part of an innovative program that’s improved the health of millions of children in their country.

You can meet them yourself (and join us for a cup of coffee) in this virtual reality film.

Back in 1990, Ethiopia had one of the highest rates of child mortality in the world. One in five children were dying before their 5th birthdays. With few doctors and most of its population living in rural areas, Ethiopia struggled to provide basic health services to the country. Most women in rural areas gave birth at home.

Then in 2000, the Ethiopian government made a commitment to improve its healthcare system. Ethiopia signed on to the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals, which focused the world’s attention on fighting disease and ending poverty by using data to measure progress on health and development progress. As part of the goals, Ethiopia pledged to reduce under-five death rates by at least two-thirds by 2015.

To achieve it, Ethiopia needed to find an effective way to deliver healthcare to the remotest corners of the country. But training thousands of new doctors to staff them would take years and would be extremely costly. Instead, Ethiopia created a community health worker program. They selected thousands of people, primarily young women with at least a 10th grade education, and trained them in a set of basic health skills—including how to deliver babies, administer immunizations, and provide family planning support—that are proven to save lives. Most of the health workers were recruited from the communities they served, helping to quickly build public trust in the new effort.

In 2012, I made my first trip to Ethiopia to see the program in action for myself. I was amazed. I visited a remote health post south of Addis Ababa run by two health workers, Yetagesu Alemu and Betula Shemesie. They spent many of their days walking from door to door in their village caring for pregnant women and families with newborns. Their health post didn’t have electricity or any high tech medical equipment. Still, their efforts had made an impact on the health of the families in their community.

What was exciting to see was how this success was being repeated in villages across the country. Despite being one of the poorest countries in the world, Ethiopia managed to dramatically reduce the rate of child mortality. By 2012, Ethiopia had met the target for the Millennium Development Goal on child survival, with under-five death rates dropping by 66 percent since 1990.

One of the key reasons the program has been so effective is that the health workers are dedicated to measuring their progress. Covering nearly every square inch of the walls of the health post I visited were large charts, where the health workers would track births, immunizations, malaria cases, and other indicators. Each indicator helped them understand how well they were performing and which areas demanded more attention.

Today, Ethiopia has more than 15,000 health posts delivering primary health care to the farthest reaches of this rural country of 100 million people. The health posts are staffed by 38,000 health workers like Betula and Yetagesu.

Last summer, I had a chance to visit Ethiopia again. I caught up with Yetagesu and Betula over coffee and to learn more about how the health worker program was going. They told me how women who once delivered their babies at home were now choosing to give birth at health centers. Their communities also had access to ambulances that would pick up any woman who is ready to give birth. Yetagesu and Betula were also proud to report that they had received additional medical training to sharpen their health skills.

To be sure, there’s a lot more work to be done to improve health services in rural Ethiopia. Their communities need more ambulances. Just one vehicle serves 17 health posts, Yetagesu said. They also hoped the country would hire more health workers so they would have the time to provide families with more comprehensive services. And as Melinda and I discussed in this year’s annual letter, one of the biggest challenge in child survival is newborn deaths. In Ethiopia, about 44 percent of all childhood deaths occur within the first 28 days of life. We need to find innovative ways to solve this challenge.

Still, I’m confident that Ethiopia will continue to make progress in child survival. And what’s most exciting is that Ethiopia’s health program has been so successful that it now serves as a model for other countries to follow. Sharing lifesaving innovations like Ethiopia’s ensures that in the years ahead the most beautiful chart in the world will become even more beautiful.